4. Conditionals¶

4.1. The modulus operator¶

The modulus operator works on integers (and integer expressions) and yields

the remainder when the first operand is divided by the second. In Python, the

modulus operator is a percent sign (%). The syntax is the same as for other

operators:

>>> quotient = 7 / 3

>>> print(quotient)

2

>>> remainder = 7 % 3

>>> print(remainder)

1

So 7 divided by 3 is 2 with 1 left over.

The modulus operator turns out to be surprisingly useful. For example, you can

check whether one number is divisible by another—if x % y is zero, then

x is divisible by y.

Also, you can extract the right-most digit or digits from a number. For

example, x % 10 yields the right-most digit of x (in base 10).

Similarly x % 100 yields the last two digits.

4.2. Boolean values and expressions¶

The Python type for storing true and false values is called bool, named

after the British mathematician, George Boole. George Boole created Boolean

algebra, which is the basis of all modern computer arithmetic.

There are only two boolean values: True and False. Capitalization

is important, since true and false are not boolean values.

>>> type(True)

<type 'bool'>

>>> type(true)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'true' is not defined

A boolean expression is an expression that evaluates to a boolean value.

The operator == compares two values and produces a boolean value:

>>> 5 == 5

True

>>> 5 == 6

False

In the first statement, the two operands are equal, so the expression evaluates

to True; in the second statement, 5 is not equal to 6, so we get False.

The == operator is one of the comparison operators; the others are:

x != y # x is not equal to y

x > y # x is greater than y

x < y # x is less than y

x >= y # x is greater than or equal to y

x <= y # x is less than or equal to y

Although these operations are probably familiar to you, the Python symbols are

different from the mathematical symbols. A common error is to use a single

equal sign (=) instead of a double equal sign (==). Remember that =

is an assignment operator and == is a comparison operator. Also, there is

no such thing as =< or =>.

4.3. Logical operators¶

There are three logical operators: and, or, and not. The

semantics (meaning) of these operators is similar to their meaning in English.

For example, x > 0 and x < 10 is true only if x is greater than 0 and

less than 10.

n % 2 == 0 or n % 3 == 0 is true if either of the conditions is true,

that is, if the number is divisible by 2 or 3.

Finally, the not operator negates a boolean expression, so not(x > y)

is true if (x > y) is false, that is, if x is less than or equal to

y.

4.4. Conditional execution¶

In order to write useful programs, we almost always need the ability to check

conditions and change the behavior of the program accordingly. Conditional

statements give us this ability. The simplest form is the ** if

statement**:

if x > 0:

print("%s is positive" % (x))

(See Chapter 7.13 for more information on string formatting.)

The boolean expression after the if statement is called the condition.

If it is true, then the indented statement gets executed. If not, nothing

happens.

The syntax for an if statement looks like this:

if BOOLEAN EXPRESSION:

STATEMENTS

As with the function definition from last chapter and other compound

statements, the if statement consists of a header and a body. The header

begins with the keyword if followed by a boolean expression and ends with

a colon (:).

The indented statements that follow are called a block. The first unindented statement marks the end of the block. A statement block inside a compound statement is called the body of the statement.

Each of the statements inside the body are executed in order if the boolean

expression evaluates to True. The entire block is skipped if the boolean

expression evaluates to False.

There is no limit on the number of statements that can appear in the body of an

if statement, but there has to be at least one. Occasionally, it is useful

to have a body with no statements (usually as a place keeper for code you

haven’t written yet). In that case, you can use the pass statement, which

does nothing.

if True: # This is always true

pass # so this is always executed, but it does nothing

4.5. Alternative execution¶

A second form of the if statement is alternative execution, in which there

are two possibilities and the condition determines which one gets executed. The

syntax looks like this:

if x % 2 == 0:

print("%s is even" % (x))

else:

print("%s is odd" % (x))

If the remainder when x is divided by 2 is 0, then we know that x is

even, and the program displays a message to that effect. If the condition is

false, the second set of statements is executed. Since the condition must be

true or false, exactly one of the alternatives will be executed. The

alternatives are called branches, because they are branches in the flow of

execution.

As an aside, if you need to check the parity (evenness or oddness) of numbers often, you might wrap this code in a function:

def print_parity(x):

if x % 2 == 0:

print("%s is even" % (x))

else:

print("%s is odd" % (x))

For any value of x, print_parity displays an appropriate message.

When you call it, you can provide any integer expression as an argument.

>>> print_parity(17)

17 is odd

>>> y = 41

>>> print_parity(y+1)

42 is even

4.6. Chained conditionals¶

Sometimes there are more than two possibilities and we need more than two branches. One way to express a computation like that is a chained conditional:

if x < y:

print("%s is less than %s" % (x, y))

elif x > y:

print("%s is greater than %s" % (x, y))

else:

print("%s and %s are equal" % (x,y))

elif is an abbreviation of else if . Again, exactly one branch will be

executed. There is no limit of the number of elif statements but only a

single (and optional) else statement is allowed and it must be the last

branch in the statement:

if choice == 'a':

function_a()

elif choice == 'b':

function_b()

elif choice == 'c':

function_c()

else:

print("Invalid choice.")

Each condition is checked in order. If the first is false, the next is checked, and so on. If one of them is true, the corresponding branch executes, and the statement ends. Even if more than one condition is true, only the first true branch executes.

4.7. Nested conditionals¶

One conditional can also be nested within another. We could have written the trichotomy example as follows:

if x == y:

print("%s and %s are equal" % (x,y))

else:

if x < y:

print("%s is less than %s" % (x, y))

else:

print("%s is greater than %s" % (x, y))

The outer conditional contains two branches. The first branch contains a simple

output statement. The second branch contains another if statement, which

has two branches of its own. Those two branches are both output statements,

although they could have been conditional statements as well.

Although the indentation of the statements makes the structure apparent, nested conditionals become difficult to read very quickly. In general, it is a good idea to avoid them when you can.

Logical operators often provide a way to simplify nested conditional statements. For example, we can rewrite the following code using a single conditional:

if 0 < x:

if x < 10:

print("x is a positive single digit.")

The print statement is executed only if we make it past both the

conditionals, so we can use the and operator:

if 0 < x and x < 10:

print("x is a positive single digit.")

These kinds of conditions are common, so Python provides an alternative syntax that is similar to mathematical notation:

if 0 < x < 10:

print("x is a positive single digit.")

This condition is semantically the same as the compound boolean expression and the nested conditional.

4.8. The return statement¶

The return statement allows you to terminate the execution of a function

before you reach the end. One reason to use it is if you detect an error

condition:

def print_square_root(x):

if x <= 0:

print("Positive numbers only, please.")

return

result = x**0.5

print("The square root of %s is %s" % (x, result))

The function print_square_root has a parameter named x. The first thing

it does is check whether x is less than or equal to 0, in which case it

displays an error message and then uses return to exit the function. The

flow of execution immediately returns to the caller, and the remaining lines of

the function are not executed.

4.9. Keyboard input¶

In Input we were introduced to Python’s built-in function that gets

input from the keyboard: raw_input(). Let’s look at this

again in greater depth.

When raw_input() is called, the program stops and waits for the

user to type something. When the user presses Return or the Enter key, the

program resumes and raw_input() returns what the user typed as a string:

>>> my_input = raw_input()

3.14159

>>> print(my_input)

3.14159

>>> type(my_input)

<type 'str'>

It is always a good idea to tell the user what to input.

We can supply a prompt as a single argument to raw_input():

>>> name = raw_input("What...is your name? ")

What...is your name? Arthur, King of the Britons!

>>> print(name)

Arthur, King of the Britons!

Notice that the prompt is a string, so it must be enclosed in quotation marks.

If we expect the user response to be an integer or a float, we can still call raw_input(),

and then use conversion functions to convert what raw_input() returns to other types.

4.10. Type conversion¶

Each Python type comes with a built-in command that attempts to convert values

of another type into that type. The int(ARGUMENT) command, for example,

takes any value and converts it to an integer, if possible, or complains

otherwise:

>>> int("32")

32

>>> int("Hello")

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'Hello'

int can also convert floating-point values to integers, but remember

that it truncates the fractional part:

>>> int(-2.3)

-2

>>> int(3.99999)

3

>>> int("42")

42

>>> int(1.0)

1

The float(ARGUMENT) command converts integers and strings to floating-point

numbers:

>>> float(32)

32.0

>>> float("3.14159")

3.14159

>>> float(1)

1.0

It may seem odd that Python distinguishes the integer value 1 from the

floating-point value 1.0. They may represent the same number, but they

belong to different types. The reason is that they are represented differently

inside the computer.

The str(ARGUMENT) command converts any argument given to it to type

string:

>>> str(32)

'32'

>>> str(3.14149)

'3.14149'

>>> str(True)

'True'

>>> str(true)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'true' is not defined

str(ARGUMENT) will work with any value and convert it into a string. As

mentioned earlier, True is boolean value; true is not.

For boolean values, the situation is especially interesting:

>>> bool(1)

True

>>> bool(0)

False

>>> bool("Ni!")

True

>>> bool("")

False

>>> bool(3.14159)

True

>>> bool(0.0)

False

Python assigns boolean values to values of other types. For numerical types like integers and floating-points, zero values are false and non-zero values are true. For strings, empty strings are false and non-empty strings are true.

NOTE: calling one of these conversion functions on data stored in a variable does not change what’s stored in the variable! It takes what is stored in the variable and converts it, but does not automatically reassign the result back to the variable:

>>> x = "3.14159"

>>> float(x)

3.14159

>>> type(x)

<type 'str'>

If you want x to contain the float 3.14159, you can convert it and reassign it like this:

>>> x = float(x)

>>> print(x)

3.14159

>>> type(x)

<type 'float'>

4.11. GASP¶

GASP (Graphics API for Students of Python) will enable us to write programs involving graphics. Before you can use GASP, it needs to be installed on your machine. If you are running Ubuntu GNU/Linux, see GASP in Appendix A. Current instructions for installing GASP on other platforms can be found at http://dev.laptop.org/pub/gasp/downloads.

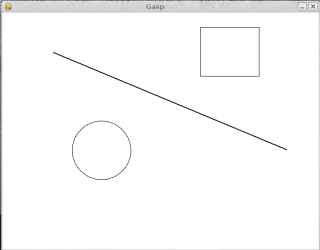

After installing gasp, try the following python script:

from gasp import *

begin_graphics()

Circle((200, 200), 60)

Line((100, 400), (580, 200))

Box((400, 350), 120, 100)

update_when('key_pressed')

end_graphics()

The second to the last command pauses and waits until a key is pressed. Without it, the screen would flash by so quickly you wouldn’t see it.

Running this script, you should see a graphics window that looks like this:

We will be using gasp from here on to illustrate (pun intended) computer programming concepts and to add to our fun while learning. You can find out more about the GASP module by reading Appendix B.

4.12. Glossary¶

- block

- A group of consecutive statements with the same indentation.

- body

- The block of statements in a compound statement that follows the header.

- boolean expression

- An expression that is either true or false.

- boolean value

- There are exactly two boolean values:

TrueandFalse. Boolean values result when a boolean expression is evaluated by the Python interepreter. They have typebool. - branch

- One of the possible paths of the flow of execution determined by conditional execution.

- chained conditional

- A conditional branch with more than two possible flows of execution. In

Python chained conditionals are written with

if ... elif ... elsestatements. - comparison operator

- One of the operators that compares two values:

==,!=,>,<,>=, and<=. - condition

- The boolean expression in a conditional statement that determines which branch is executed.

- conditional statement

- A statement that controls the flow of execution depending on some

condition. In Python the keywords

if,elif, andelseare used for conditional statements. - logical operator

- One of the operators that combines boolean expressions:

and,or, andnot. - modulus operator

- An operator, denoted with a percent sign (

%), that works on integers and yields the remainder when one number is divided by another. - nesting

- One program structure within another, such as a conditional statement inside a branch of another conditional statement.

- prompt

- A visual cue that tells the user to input data.

- type conversion

- An explicit statement that takes a value of one type and computes a corresponding value of another type.

- wrapping code in a function

- The process of adding a function header and parameters to a sequence of program statements is often refered to as “wrapping the code in a function”. This process is very useful whenever the program statements in question are going to be used multiple times.

4.13. Exercises¶

Try to evaluate the following numerical expressions in your head, then use the Python interpreter to check your results:

>>> 5 % 2>>> 9 % 5>>> 15 % 12>>> 12 % 15>>> 6 % 6>>> 0 % 7>>> 7 % 0

What happened with the last example? Why? If you were able to correctly anticipate the computer’s response in all but the last one, it is time to move on. If not, take time now to make up examples of your own. Explore the modulus operator until you are confident you understand how it works.

if x < y: print("%s is less than %s" % (x, y)) elif x > y: print("%s is greater than %s" % (x, y)) else: print("%s and %s are equal" % (x, y))

Wrap this code in a function called

compare(x, y). Callcomparethree times: one each where the first argument is less than, greater than, and equal to the second argument.To better understand boolean expressions, it is helpful to construct truth tables. Two boolean expressions are logically equivalent if and only if they have the same truth table.

The following Python script prints out the truth table for any boolean expression in two variables: p and q:

expression = raw_input("Enter a boolean expression in two variables, p and q: ") print(" p q %s" % (expression)) length = len(" p q %s" % (expression)) print(length*"=") for p in True, False: for q in True, False: print("%-7s %-7s %-7s" % (p, q, eval(expression)))

You will learn how this script works in later chapters. For now, you will use it to learn about boolean expressions. Copy this program to a file named

p_and_q.py, then run it from the command line and give it:p or q, when prompted for a boolean expression. You should get the following output:p q p or q ===================== True True True True False True False True True False False False

Now that we see how it works, let’s wrap it in a function to make it easier to use:

def truth_table(expression): print(" p q %s" % (expression)) length = len( " p q %s" % expression) print(length*"=") for p in True, False: for q in True, False: print("%-7s %-7s %-7s" % (p, q, eval(expression)))

We can import it into a Python shell and call

truth_tablewith a string containing our boolean expression in p and q as an argument:>>> from p_and_q import * >>> truth_table("p or q") p q p or q ===================== True True True True False True False True True False False False >>>

Use the

truth_tablefunctions with the following boolean expressions, recording the truth table produced each time:- not(p or q)

- p and q

- not(p and q)

- not(p) or not(q)

- not(p) and not(q)

Which of these are logically equivalent?

Enter the following expressions into the Python shell:

True or False True and False not(False) and True True or 7 False or 7 True and 0 False or 8 "happy" and "sad" "happy" or "sad" "" and "sad" "happy" and ""

Analyze these results. What observations can you make about values of different types and logical operators? Can you write these observations in the form of simple rules about

andandorexpressions?if choice == 'a': function_a() elif choice == 'b': function_b() elif choice == 'c': function_c() else: print("Invalid choice.")

Wrap this code in a function called

dispatch(choice). Then definefunction_a,function_b, andfunction_cso that they print out a message saying they were called. For example:def function_a(): print("function_a was called...")

Put the four functions (

dispatch,function_a,function_b, andfunction_cinto a script namedch04e05.py. At the bottom of this script add a call todispatch('b'). Your output should be:function_b was called...

Finally, modify the script so that user can enter ‘a’, ‘b’, or ‘c’. Test it by importing your script into the Python shell.

Write a function named

is_divisible_by_3that takes a single integer as an argument and prints “This number is divisible by three.” if the argument is evenly divisible by 3 and “This number is not divisible by three.” otherwise.Now write a similar function named

is_divisible_by_5.Generalize the functions you wrote in the previous exercise into a function named

is_divisible_by_n(x, n)that takes two integer arguments and prints out whether the first is divisible by the second. Save this in a file namedch04e07.py. Import it into a shell and try it out. A sample session might look like this:>>> from ch04e07 import * >>> is_divisible_by_n(20, 4) Yes, 20 is divisible by 4 >>> is_divisible_by_n(21, 8) No, 21 is not divisible by 8

What will be the output of the following?

if "Ni!": print('We are the Knights who say, "Ni!"') else: print("Stop it! No more of this!") if 0: print("And now for something completely different...") else: print("What's all this, then?")

Explain what happened and why it happened.

The following gasp script, in a file named

house.py, draws a simple house on a gasp canvas:from gasp import * # import everything from the gasp library begin_graphics() # open the graphics canvas Box((20, 20), 100, 100) # the house Box((55, 20), 30, 50) # the door Box((40, 80), 20, 20) # the left window Box((80, 80), 20, 20) # the right window Line((20, 120), (70, 160)) # the left roof Line((70, 160), (120, 120)) # the right roof update_when('key_pressed') # keep the canvas open until a key is pressed end_graphics() # close the canvas (which would happen # anyway, since the script ends here, but it # is better to be explicit).

Run this script and confirm that you get a window that looks like this:

- Wrap the house code in a function named

draw_house(). - Run the script now. Do you see a house? Why not?

- Add a call to

draw_house()at the botton of the script so that the house returns to the screen. - Parameterize the function with x and y parameters – the header

should then become

def draw_house(x, y):, so that you can pass in the location of the house on the canvas. - Use

draw_houseto place five houses on the canvas in different locations.

- Wrap the house code in a function named

Exploration: Read over Appendix B and write a script named

houses.pythat produces the following when run:

hint: You will need to use a

Polygonfor the roof instead of twoLines to getfilled=Trueto work with it.