9. Lists¶

A list is an ordered set of values, where each value is identified by an index. The values that make up a list are called its elements. Lists are similar to strings, which are ordered sets of characters, except that the elements of a list can have any type. Lists and strings — and other things that behave like ordered sets — are called sequences.

9.1. List values¶

There are several ways to create a new list; the simplest is to enclose the

elements in square brackets ( [ and ]):

[10, 20, 30, 40]

["spam", "bungee", "swallow"]

The first example is a list of four integers. The second is a list of three strings. The elements of a list don’t have to be the same type. The following list contains a string, a float, an integer, and (mirabile dictu) another list:

["hello", 2.0, 5, [10, 20]]

A list within another list is said to be nested.

Finally, there is a special list that contains no elements. It is called the

empty list, and is denoted [].

Like numeric 0 values and the empty string, the empty list is false in a boolean expression:

>>> if []:

... print('This is true.')

... else:

... print('This is false.')

...

This is false.

>>>

With all these ways to create lists, it would be disappointing if we couldn’t assign list values to variables or pass lists as parameters to functions. We can:

>>> vocabulary = ["ameliorate", "castigate", "defenestrate"]

>>> numbers = [17, 123]

>>> empty = []

>>> print(vocabulary)

['ameliorate', 'castigate', 'defenestrate']

>>> print(numbers)

[17, 123]

>>> print(empty)

[]

9.2. Accessing elements¶

The syntax for accessing the elements of a list is the same as the syntax for

accessing the characters of a string—the bracket operator ( [] – not to

be confused with an empty list). The expression inside the brackets specifies

the index. Remember that the indices start at 0:

>>> print(numbers[0])

17

Any integer expression can be used as an index:

>>> numbers[9-8]

123

>>> numbers[1.0]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: list indices must be integers

If you try to read or write an element that does not exist, you get a runtime error:

>>> numbers[2]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

IndexError: list index out of range

If an index has a negative value, it counts backward from the end of the list:

>>> numbers[-1]

123

>>> numbers[-2]

17

>>> numbers[-3]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

IndexError: list index out of range

numbers[-1] is the last element of the list, numbers[-2] is the second

to last, and numbers[-3] doesn’t exist.

It is common to use a loop variable as a list index.

horsemen = ["war", "famine", "pestilence", "death"]

i = 0

while i < 4:

print(horsemen[i])

i += 1

This while loop counts from 0 to 4. When the loop variable i is 4, the

condition fails and the loop terminates. So the body of the loop is only

executed when i is 0, 1, 2, and 3.

Each time through the loop, the variable i is used as an index into the

list, printing the i-eth element. This pattern of computation is called a

list traversal.

9.3. List length¶

The function len returns the length of a list, which is equal to the number

of its elements. It is a good idea to use this value as the upper bound of a

loop instead of a constant. That way, if the size of the list changes, you

won’t have to go through the program changing all the loops; they will work

correctly for any size list:

horsemen = ["war", "famine", "pestilence", "death"]

i = 0

num = len(horsemen)

while i < num:

print(horsemen[i])

i += 1

The last time the body of the loop is executed, i is len(horsemen) - 1,

which is the index of the last element. When i is equal to

len(horsemen), the condition fails and the body is not executed, which is a

good thing, because len(horsemen) is not a legal index.

Although a list can contain another list, the nested list still counts as a single element. The length of this list is 4:

['spam!', 1, ['Brie', 'Roquefort', 'Pol le Veq'], [1, 2, 3]]

9.4. List membership¶

in is a boolean operator that tests membership in a sequence. We

used it previously with strings, but it also works with lists and

other sequences:

>>> horsemen = ['war', 'famine', 'pestilence', 'death']

>>> 'pestilence' in horsemen

True

>>> 'debauchery' in horsemen

False

Since pestilence is a member of the horsemen list, the in operator

returns True. Since debauchery is not in the list, in returns

False.

We can use the not in combination with in to test whether an element is

not a member of a list:

>>> 'debauchery' not in horsemen

True

9.5. List operations¶

The + operator concatenates lists:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = [4, 5, 6]

>>> c = a + b

>>> print(c)

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Similarly, the * operator repeats a list a given number of times:

>>> [0] * 4

[0, 0, 0, 0]

>>> [1, 2, 3] * 3

[1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3]

The first example repeats [0] four times. The second example repeats the

list [1, 2, 3] three times.

9.6. List slices¶

The slice operations we saw with strings also work on lists:

>>> a_list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> a_list[1:3]

['b', 'c']

>>> a_list[:4]

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>> a_list[3:]

['d', 'e', 'f']

>>> a_list[:]

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

9.7. The range function¶

Lists that contain consecutive integers are common, so Python provides a simple way to create them:

>>> range(1, 5)

[1, 2, 3, 4]

The range function takes two arguments and returns a list that contains all

the integers from the first to the second, including the first but not the

second.

There are two other forms of range. With a single argument, it creates a

list that starts at 0:

>>> range(10)

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

If there is a third argument, it specifies the space between successive values, which is called the step size. This example counts from 1 to 10 by steps of 2:

>>> range(1, 10, 2)

[1, 3, 5, 7, 9]

If the step size is negative, then start must be greater than stop

>>> range(20, 4, -5)

[20, 15, 10, 5]

or the result will be an empty list.

>>> range(10, 20, -5)

[]

9.8. Lists are mutable¶

Unlike strings, lists are mutable, which means we can change their elements. Using the bracket operator on the left side of an assignment, we can update one of the elements:

>>> fruit = ["banana", "apple", "quince"]

>>> fruit[0] = "pear"

>>> fruit[-1] = "orange"

>>> print(fruit)

['pear', 'apple', 'orange']

The bracket operator applied to a list can appear anywhere in an expression.

When it appears on the left side of an assignment, it changes one of the

elements in the list, so the first element of fruit has been changed from

'banana' to 'pear', and the last from 'quince' to 'orange'. An

assignment to an element of a list is called item assignment. Item

assignment does not work for strings:

>>> my_string = 'TEST'

>>> my_string[2] = 'X'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

but it does for lists:

>>> my_list = ['T', 'E', 'S', 'T']

>>> my_list[2] = 'X'

>>> my_list

['T', 'E', 'X', 'T']

With the slice operator we can update several elements at once:

>>> a_list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> a_list[1:3] = ['x', 'y']

>>> print(a_list)

['a', 'x', 'y', 'd', 'e', 'f']

We can also remove elements from a list by assigning the empty list to them:

>>> a_list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> a_list[1:3] = []

>>> print(a_list)

['a', 'd', 'e', 'f']

And we can add elements to a list by squeezing them into an empty slice at the desired location:

>>> a_list = ['a', 'd', 'f']

>>> a_list[1:1] = ['b', 'c']

>>> print(a_list)

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'f']

>>> a_list[4:4] = ['e']

>>> print(a_list)

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

9.9. List deletion¶

Using slices to delete list elements can be awkward, and therefore error-prone. Python provides an alternative that is more readable.

del removes an element from a list:

>>> a = ['one', 'two', 'three']

>>> del a[1]

>>> a

['one', 'three']

As you might expect, del handles negative indices and causes a runtime

error if the index is out of range.

You can use a slice as an index for del:

>>> a_list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> del a_list[1:5]

>>> print(a_list)

['a', 'f']

As usual, slices select all the elements up to, but not including, the second index.

9.10. Objects and values¶

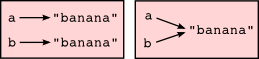

If we execute these assignment statements,

a = "banana"

b = "banana"

we know that a and b will refer to a string with the letters

"banana". But we don’t know yet whether they point to the same string.

There are two possible states:

In one case, a and b refer to two different things that have the same

value. In the second case, they refer to the same thing. These things have

names — they are called objects. An object is something a variable can

refer to.

We can test whether two names have the same value using ==:

>>> a == b

True

We can test whether two names refer to the same object using the is operator:

>>> a is b

True

This tells us that both a and b refer to the same object, and that it

is the second of the two state diagrams that describes the relationship.

Since strings are immutable, Python optimizes resources by making two names that refer to the same string value refer to the same object.

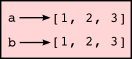

This is not the case with lists:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = [1, 2, 3]

>>> a == b

True

>>> a is b

False

The state diagram here looks like this:

a and b have the same value but do not refer to the same object.

9.11. Aliasing¶

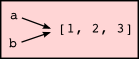

Since variables refer to objects, if we assign one variable to another, both variables refer to the same object:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = a

>>> a is b

True

In this case, the state diagram looks like this:

Because the same list has two different names, a and b, we say that it

is aliased. Changes made with one alias affect the other:

>>> b[0] = 5

>>> print(a)

[5, 2, 3]

Although this behavior can be useful, it is sometimes unexpected or undesirable. In general, it is safer to avoid aliasing when you are working with mutable objects. Of course, for immutable objects, there’s no problem. That’s why Python is free to alias strings when it sees an opportunity to economize.

9.12. Cloning lists¶

If we want to modify a list and also keep a copy of the original, we need to be able to make a copy of the list itself, not just the reference. This process is sometimes called cloning, to avoid the ambiguity of the word copy.

The easiest way to clone a list is to use the slice operator:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = a[:]

>>> print(b)

[1, 2, 3]

Taking any slice of a creates a new list. In this case the slice happens to

consist of the whole list.

Now we are free to make changes to b without worrying about a:

>>> b[0] = 5

>>> print(a)

[1, 2, 3]

9.13. Lists and for loops¶

The for loop also works with lists. The generalized syntax of a for

loop is:

for VARIABLE in LIST:

BODY

This statement is equivalent to:

i = 0

while i < len(LIST):

VARIABLE = LIST[i]

BODY

i += 1

The for loop is more concise because we can eliminate the loop variable,

i. Here is an equivalent to the while loop from the

Accessing elements section written with a for loop.

for horseman in horsemen:

print(horseman)

It almost reads like English: For (every) horseman in (the list of) horsemen, print (the name of the) horseman.

Any list expression can be used in a for loop:

for number in range(20):

if number % 3 == 0:

print(number)

for fruit in ["banana", "apple", "quince"]:

print("I like to eat " + fruit + "s!")

The first example prints all the multiples of 3 between 0 and 19. The second example expresses enthusiasm for various fruits.

Since lists are mutable, it is often desirable to traverse a list, modifying

each of its elements. The following squares all the numbers from 1 to

5:

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

for index in range(len(numbers)):

numbers[index] = numbers[index]**2

Take a moment to think about range(len(numbers)) until you understand how

it works. We are interested here in both the value and its index within the

list, so that we can assign a new value to it.

This pattern is common enough that Python provides a nicer way to implement it:

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

for index, value in enumerate(numbers):

numbers[index] = value**2

enumerate generates both the index and the value associated with it during

the list traversal. Try this next example to see more clearly how enumerate

works:

>>> for index, value in enumerate(['banana', 'apple', 'pear', 'quince']):

... print("%d %s" % (index, value))

...

0 banana

1 apple

2 pear

3 quince

>>>

9.14. List parameters¶

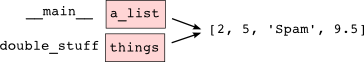

Passing a list as an argument actually passes a reference to the list, not a copy of the list. Since lists are mutable changes made to the parameter change the argument as well. For example, the function below takes a list as an argument and multiplies each element in the list by 2:

def double_stuff(a_list):

for index, value in enumerate(a_list):

a_list[index] = 2 * value

If we put double_stuff in a file named ch09.py, we can test it out like

this:

>>> from ch09 import double_stuff

>>> things = [2, 5, 'Spam', 9.5]

>>> double_stuff(things)

>>> things

[4, 10, 'SpamSpam', 19.0]

>>>

The parameter a_list and the variable things are aliases for the

same object. The state diagram looks like this:

Since the list object is shared by two frames, we drew it between them.

If a function modifies a list parameter, the caller sees the change.

9.15. Pure functions and modifiers¶

Functions which take lists as arguments and change them during execution are called modifiers and the changes they make are called side effects.

A pure function does not produce side effects. It communicates with the

calling program only through parameters, which it does not modify, and a return

value. Here is double_stuff written as a pure function:

def double_stuff(a_list):

new_list = []

for value in a_list:

new_list += [2 * value]

return new_list

This version of double_stuff does not change its arguments:

>>> from ch09 import double_stuff

>>> things = [2, 5, 'Spam', 9.5]

>>> double_stuff(things)

[4, 10, 'SpamSpam', 19.0]

>>> things

[2, 5, 'Spam', 9.5]

>>>

To use the pure function version of double_stuff to modify things,

you would assign the return value back to things:

>>> things = double_stuff(things)

>>> things

[4, 10, 'SpamSpam', 19.0]

>>>

9.16. Which is better?¶

Anything that can be done with modifiers can also be done with pure functions. In fact, some programming languages only allow pure functions. There is some evidence that programs that use pure functions are faster to develop and less error-prone than programs that use modifiers. Nevertheless, modifiers are convenient at times, and in some cases, functional programs are less efficient.

In general, we recommend that you write pure functions whenever it is reasonable to do so and resort to modifiers only if there is a compelling advantage. This approach might be called a functional programming style.

9.17. Nested lists¶

A nested list is a list that appears as an element in another list. In this list, the element with index 3 is a nested list:

>>> nested = ["hello", 2.0, 5, [10, 20]]

If we print nested[3], we get [10, 20]. To extract an element from the

nested list, we can proceed in two steps:

>>> elem = nested[3]

>>> elem[0]

10

Or we can combine them:

>>> nested[3][1]

20

Bracket operators evaluate from left to right, so this expression gets the

three-eth element of nested and extracts the one-eth element from it.

9.18. Matrices¶

Nested lists are often used to represent matrices. For example, the matrix:

might be represented as:

>>> matrix = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

matrix is a list with three elements, where each element is a row of the

matrix. We can select an entire row from the matrix in the usual way:

>>> matrix[1]

[4, 5, 6]

Or we can extract a single element from the matrix using the double-index form:

>>> matrix[1][1]

5

The first index selects the row, and the second index selects the column. Although this way of representing matrices is common, it is not the only possibility. A small variation is to use a list of columns instead of a list of rows. Later we will see a more radical alternative using a dictionary.

9.19. Test-driven development (TDD)¶

Test-driven development (TDD) is a software development practice which arrives at a desired feature through a series of small, iterative steps motivated by automated tests which are written first that express increasing refinements of the desired feature.

Doctest enables us to easily demonstrate TDD. Let’s say we want a function

which creates a rows by columns matrix given arguments for rows and

columns.

We first setup a test for this function in a file named matrices.py:

def make_matrix(rows, columns):

"""

>>> make_matrix(3, 5)

[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

"""

if __name__ == '__main__':

import doctest

doctest.testmod()

Running this returns in a failing test:

**********************************************************************

File "matrices.py", line 3, in __main__.make_matrix

Failed example:

make_matrix(3, 5)

Expected:

[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

Got nothing

**********************************************************************

1 items had failures:

1 of 1 in __main__.make_matrix

***Test Failed*** 1 failures.

The test fails because the body of the function contains only a single triple

quoted string and no return statement, so it returns None. Our test

indicates that we wanted it to return a matrix with 3 rows of 5 columns of

zeros.

The rule in using TDD is to use the simplest thing that works in writing a solution to pass the test, so in this case we can simply return the desired result:

def make_matrix(rows, columns):

"""

>>> make_matrix(3, 5)

[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

"""

return [[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

Running this now the test passes, but our current implementation of

make_matrix always returns the same result, which is clearly not what we

intended. To fix this, we first motivate our improvement by adding a test:

def make_matrix(rows, columns):

"""

>>> make_matrix(3, 5)

[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

>>> make_matrix(4, 2)

[[0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0]]

"""

return [[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

which as we expect fails:

**********************************************************************

File "matrices.py", line 5, in __main__.make_matrix

Failed example:

make_matrix(4, 2)

Expected:

[[0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0]]

Got:

[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

**********************************************************************

1 items had failures:

1 of 2 in __main__.make_matrix

***Test Failed*** 1 failures.

This technique is called test-driven because code should only be written when there is a failing test to make pass. Motivated by the failing test, we can now produce a more general solution:

def make_matrix(rows, columns):

"""

>>> make_matrix(3, 5)

[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

>>> make_matrix(4, 2)

[[0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0]]

"""

return [[0] * columns] * rows

This solution appears to work, and we may think we are finished, but when we use the new function later we discover a bug:

>>> from matrices import *

>>> m = make_matrix(4, 3)

>>> m

[[0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0]]

>>> m[1][2] = 7

>>> m

[[0, 0, 7], [0, 0, 7], [0, 0, 7], [0, 0, 7]]

>>>

We wanted to assign the element in the second row and the third column the value 7, instead, all elements in the third column are 7!

Upon reflection, we realize that in our current solution, each row is an alias of the other rows. This is definitely not what we intended, so we set about fixing the problem, first by writing a failing test:

def make_matrix(rows, columns):

"""

>>> make_matrix(3, 5)

[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

>>> make_matrix(4, 2)

[[0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0]]

>>> m = make_matrix(4, 2)

>>> m[1][1] = 7

>>> m

[[0, 0], [0, 7], [0, 0], [0, 0]]

"""

return [[0] * columns] * rows

With a failing test to fix, we are now driven to a better solution:

def make_matrix(rows, columns):

"""

>>> make_matrix(3, 5)

[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

>>> make_matrix(4, 2)

[[0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0]]

>>> m = make_matrix(4, 2)

>>> m[1][1] = 7

>>> m

[[0, 0], [0, 7], [0, 0], [0, 0]]

"""

matrix = []

for row in range(rows):

matrix += [[0] * columns]

return matrix

Using TDD has several benefits to our software development process. It:

- helps us think concretely about the problem we are trying to solve before we attempt to solve it.

- encourages breaking down complex problems into smaller, simpler problems and working our way toward a solution of the larger problem step-by-step.

- assures that we have a well developed automated test suite for our software, facilitating later additions and improvements.

9.20. Strings and lists¶

Python has a command called list that takes a sequence type as an argument

and creates a list out of its elements.

>>> list("Crunchy Frog")

['C', 'r', 'u', 'n', 'c', 'h', 'y', ' ', 'F', 'r', 'o', 'g']

There is also a str command that takes any Python value as an argument and

returns a string representation of it.

>>> str(5)

'5'

>>> str(None)

'None'

>>> str(list("nope"))

"['n', 'o', 'p', 'e']"

As we can see from the last example, str can’t be used to join a list of

characters together. To do this we could use the join function in the

string module:

>>> import string

>>> char_list = list("Frog")

>>> char_list

['F', 'r', 'o', 'g']

>>> string.join(char_list, '')

'Frog'

Two of the most useful functions in the string module involve lists of

strings. The split function breaks a string into a list of words. By

default, any number of whitespace characters is considered a word boundary:

>>> import string

>>> song = "The rain in Spain..."

>>> string.split(song)

['The', 'rain', 'in', 'Spain...']

An optional argument called a delimiter can be used to specify which

characters to use as word boundaries. The following example uses the string

ai as the delimiter:

>>> string.split(song, 'ai')

['The r', 'n in Sp', 'n...']

Notice that the delimiter doesn’t appear in the list.

string.join is the inverse of string.split. It takes two arguments: a

list of strings and a separator which will be placed between each element in

the list in the resultant string.

>>> import string

>>> words = ['crunchy', 'raw', 'unboned', 'real', 'dead', 'frog']

>>> string.join(words, ' ')

'crunchy raw unboned real dead frog'

>>> string.join(words, '**')

'crunchy**raw**unboned**real**dead**frog'

9.21. Glossary¶

- aliases

- Multiple variables that contain references to the same object.

- clone

- To create a new object that has the same value as an existing object. Copying a reference to an object creates an alias but doesn’t clone the object.

- delimiter

- A character or string used to indicate where a string should be split.

- element

- One of the values in a list (or other sequence). The bracket operator selects elements of a list.

- index

- An integer variable or value that indicates an element of a list.

- list

- A named collection of objects, where each object is identified by an index.

- list traversal

- The sequential accessing of each element in a list.

- modifier

- A function which changes its arguments inside the function body. Only mutable types can be changed by modifiers.

- mutable type

- A data type in which the elements can be modified. All mutable types are compound types. Lists are mutable data types; strings are not.

- nested list

- A list that is an element of another list.

- object

- A thing to which a variable can refer.

- pure function

- A function which has no side effects. Pure functions only make changes to the calling program through their return values.

- sequence

- Any of the data types that consist of an ordered set of elements, with each element identified by an index.

- side effect

- A change in the state of a program made by calling a function that is not a result of reading the return value from the function. Side effects can only be produced by modifiers.

- step size

- The interval between successive elements of a linear sequence. The

third (and optional argument) to the

rangefunction is called the step size. If not specified, it defaults to 1. - test-driven development (TDD)

- A software development practice which arrives at a desired feature through a series of small, iterative steps motivated by automated tests which are written first that express increasing refinements of the desired feature. (see the Wikipedia article on Test-driven development for more information.)

9.22. Exercises¶

Write a loop that traverses:

['spam!', 1, ['Brie', 'Roquefort', 'Pol le Veq'], [1, 2, 3]]

and prints the length of each element. What happens if you send an integer to

len? Change1to'one'and run your solution again.Open a file named

ch09e02.pyand with the following content:# Add your doctests here: """ """ # Write your Python code here: if __name__ == '__main__': import doctest doctest.testmod()

Add each of the following sets of doctests to the docstring at the top of the file and write Python code to make the doctests pass.

""" >>> a_list[3] 42 >>> a_list[6] 'Ni!' >>> len(a_list) 8 """

""" >>> b_list[1:] ['Stills', 'Nash'] >>> group = b_list + c_list >>> group[-1] 'Young' """

""" >>> 'war' in mystery_list False >>> 'peace' in mystery_list True >>> 'justice' in mystery_list True >>> 'oppression' in mystery_list False >>> 'equality' in mystery_list True """

""" >>> range(a, b, c) [5, 9, 13, 17] """

Only add one set of doctests at a time. The next set of doctests should not be added until the previous set pass.

What is the Python interpreter’s response to the following?

>>> range(10, 0, -2)

The three arguments to the range function are start, stop, and step, respectively. In this example,

startis greater thanstop. What happens ifstart < stopandstep < 0? Write a rule for the relationships amongstart,stop, andstep.Draw a state diagram for

aandbbefore and after the third line of the following python code is executed:a = [1, 2, 3] b = a[:] b[0] = 5

What will be the output of the following program?

this = ['I', 'am', 'not', 'a', 'crook'] that = ['I', 'am', 'not', 'a', 'crook'] print("Test 1: %s" % (this is that)) that = this print("Test 2: %s" % (this is that))

Provide a detailed explaination of the results.

Open a file named

ch09e06.pyand use the same procedure as in exercise 2 to make the following doctests pass:""" >>> 13 in junk True >>> del junk[4] >>> junk [3, 7, 9, 10, 17, 21, 24, 27] >>> del junk[a:b] >>> junk [3, 7, 27] """

""" >>> nlist[2][1] 0 >>> nlist[0][2] 17 >>> nlist[1][1] 5 """

""" >>> import string >>> string.split(message, '??') ['this', 'and', 'that'] """

Lists can be used to represent mathematical vectors. In this exercise and several that follow you will write functions to perform standard operations on vectors. Create a file named

vectors.pyand write Python code to make the doctests for each function pass.Write a function

add_vectors(u, v)that takes two lists of numbers of the same length, and returns a new list containing the sums of the corresponding elements of each.def add_vectors(u, v): """ >>> add_vectors([1, 0], [1, 1]) [2, 1] >>> add_vectors([1, 2], [1, 4]) [2, 6] >>> add_vectors([1, 2, 1], [1, 4, 3]) [2, 6, 4] >>> add_vectors([11, 0, -4, 5], [2, -4, 17, 0]) [13, -4, 13, 5] """

add_vectorsshould pass the doctests above.Write a function

scalar_mult(s, v)that takes a number,s, and a list,vand returns the scalar multiple ofvbys.def scalar_mult(s, v): """ >>> scalar_mult(5, [1, 2]) [5, 10] >>> scalar_mult(3, [1, 0, -1]) [3, 0, -3] >>> scalar_mult(7, [3, 0, 5, 11, 2]) [21, 0, 35, 77, 14] """

Write a function

dot_product(u, v)that takes two lists of numbers of the same length, and returns the sum of the products of the corresponding elements of each (the dot_product).def dot_product(u, v): """ >>> dot_product([1, 1], [1, 1]) 2 >>> dot_product([1, 2], [1, 4]) 9 >>> dot_product([1, 2, 1], [1, 4, 3]) 12 >>> dot_product([2, 0, -1, 1], [1, 5, 2, 0]) 0 """

Verify that

dot_productpasses the doctests above.Extra challenge for the mathematically inclined: Write a function

cross_product(u, v)that takes two lists of numbers of length 3 and returns their cross product. You should write your own doctests and use the test driven development process described in the chapter.Create a new module named

matrices.pyand add the following two functions introduced in the section on test-driven development:def add_row(matrix): """ >>> m = [[0, 0], [0, 0]] >>> add_row(m) [[0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0]] >>> n = [[3, 2, 5], [1, 4, 7]] >>> add_row(n) [[3, 2, 5], [1, 4, 7], [0, 0, 0]] >>> n [[3, 2, 5], [1, 4, 7]] """

def add_column(matrix): """ >>> m = [[0, 0], [0, 0]] >>> add_column(m) [[0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0]] >>> n = [[3, 2], [5, 1], [4, 7]] >>> add_column(n) [[3, 2, 0], [5, 1, 0], [4, 7, 0]] >>> n [[3, 2], [5, 1], [4, 7]] """

Your new functions should pass the doctests. Note that the last doctest in each function assures that

add_rowandadd_columnare pure functions. ( hint: Python has acopymodule with a function nameddeepcopythat could make your task easier here. We will talk more aboutdeepcopyin chapter 13, but google python copy module if you would like to try it now.)Write a function

add_matrices(m1, m2)that addsm1andm2and returns a new matrix containing their sum. You can assume thatm1andm2are the same size. You add two matrices by adding their corresponding values.def add_matrices(m1, m2): """ >>> a = [[1, 2], [3, 4]] >>> b = [[2, 2], [2, 2]] >>> add_matrices(a, b) [[3, 4], [5, 6]] >>> c = [[8, 2], [3, 4], [5, 7]] >>> d = [[3, 2], [9, 2], [10, 12]] >>> add_matrices(c, d) [[11, 4], [12, 6], [15, 19]] >>> c [[8, 2], [3, 4], [5, 7]] >>> d [[3, 2], [9, 2], [10, 12]] """

Add your new function to

matrices.pyand be sure it passes the doctests above. The last two doctests confirm thatadd_matricesis a pure function.Write a function

scalar_mult(s, m)that multiplies a matrix,m, by a scalar,s.def scalar_mult(s, m): """ >>> a = [[1, 2], [3, 4]] >>> scalar_mult(3, a) [[3, 6], [9, 12]] >>> b = [[3, 5, 7], [1, 1, 1], [0, 2, 0], [2, 2, 3]] >>> scalar_mult(10, b) [[30, 50, 70], [10, 10, 10], [0, 20, 0], [20, 20, 30]] >>> b [[3, 5, 7], [1, 1, 1], [0, 2, 0], [2, 2, 3]] """

Add your new function to

matrices.pyand be sure it passes the doctests above.Write functions

row_times_columnandmatrix_mult:def row_times_column(m1, row, m2, column): """ >>> row_times_column([[1, 2], [3, 4]], 0, [[5, 6], [7, 8]], 0) 19 >>> row_times_column([[1, 2], [3, 4]], 0, [[5, 6], [7, 8]], 1) 22 >>> row_times_column([[1, 2], [3, 4]], 1, [[5, 6], [7, 8]], 0) 43 >>> row_times_column([[1, 2], [3, 4]], 1, [[5, 6], [7, 8]], 1) 50 """

def matrix_mult(m1, m2): """ >>> matrix_mult([[1, 2], [3, 4]], [[5, 6], [7, 8]]) [[19, 22], [43, 50]] >>> matrix_mult([[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]], [[7, 8], [9, 1], [2, 3]]) [[31, 19], [85, 55]] >>> matrix_mult([[7, 8], [9, 1], [2, 3]], [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]]) [[39, 54, 69], [13, 23, 33], [14, 19, 24]] """

Add your new functions to

matrices.pyand be sure it passes the doctests above.Create a new module named

numberlists.pyand add the following functions to the module:def only_evens(numbers): """ >>> only_evens([1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8]) [4, 6, 8] >>> only_evens([2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 0]) [2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 0] >>> only_evens([1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11]) [] >>> only_evens([4, 0, -1, 2, 6, 7, -4]) [4, 0, 2, 6, -4] >>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4] >>> only_evens(nums) [2, 4] >>> nums [1, 2, 3, 4] """

def only_odds(numbers): """ >>> only_odds([1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8]) [1, 3, 7] >>> only_odds([2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 0]) [11] >>> only_odds([1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11]) [1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11] >>> only_odds([4, 0, -1, 2, 6, 7, -4]) [-1, 7] >>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4] >>> only_odds(nums) [1, 3] >>> nums [1, 2, 3, 4] """

Be sure these new functions pass the doctests.

Add a function

multiples_of(num, numlist)tonumberlists.pythat takes an integer (num), and a list of integers (numlist) as arguments and returns a list of those integers innumlistthat are multiples ofnum. Add your own doctests and use TDD to develope this function.Given:

import string song = "The rain in Spain..."

Describe the relationship between

string.join(string.split(song))andsong. Are they the same for all strings? When would they be different?Write a function

replace(s, old, new)that replaces all occurences ofoldwithnewin a strings.def replace(s, old, new): """ >>> replace('Mississippi', 'i', 'I') 'MIssIssIppI' >>> s = 'I love spom! Spom is my favorite food. Spom, spom, spom, yum!' >>> replace(s, 'om', 'am') 'I love spam! Spam is my favorite food. Spam, spam, spam, yum!' >>> replace(s, 'o', 'a') 'I lave spam! Spam is my favarite faad. Spam, spam, spam, yum!' """

Your solution should pass the doctests above. Hint: use

string.splitandstring.join.