Week 4

Quiz this coming week. Coverage: everything up to and including what we learnt last Thursday (Sep 18)

Functions

Python has a bunch of commands, but we can also write our own. They are called functions. Functions can be thought of as little "subprograms" inside our big program. They can solve little pieces of the problem for us, kind of like a "black box" that we stick information into, and it gives us the answer.

Motivation from maths: f(x) = x2

f(2) = 4

f(f(2)) = ???

- Functions have a name and a body.

- Functions are defined by putting a sequence of statements in its body.

- Statements in Python functions are indented to show that they are part of the function body.

- When the function is called or invoked, the statements inside its definition are executed sequentially (one by one from top to bottom).

- To call a function, type its name, followed by a pair of brackets ()

- Function names have to follow the same rules as variable names

Defining a Function -- the Syntax:

def <name> (<formal_parameters>):

body goes hereCalling a Function:

<name>(<actual_parameter_values>)(Programming has a name for the actual parameter values. We call them "arguments")

def hello():

print "Hello, how are you?" # remember that all the lines that "belong" to the function need to be indented.

hello() # This is not inside the function.

# When the function runs, all the statements inside the function definition are executed sequentially (from top to bottom)

# Functions can be used to make our lives easier when we write programs

def happy():

print "Happy Birthday to you"

happy()

happy()

print "Happy Birthday my dear friend"

happy()

# Obviously, changing the body of the function will affect its behavior

def happy():

print "Good morning to you"

happy()

happy()

print "Happy Birthday my dear friend"

happy()

Function Parameters

Just like functions such as int() and str() and type() can take in values, our functions can too.

When we give a function a value to work with, we say that we are passing a parameter to the function.

Parameters allow us to customize a function the way that we want.

def happy():

print "Happy Birthday to You!"

def birthday(name):

happy()

happy()

print "Happy Birthday dear", name

happy()

print "Say happy birthday to Grace"

birthday("Grace")

print "Say happy birthday to Lisa"

birthday("Lisa")

Main function

When you run a program in Python, Python scans through the program, reads in all the functions, and starts running the program at the first non-indented line that is also not a function definition.

However, many other programming languages (1) require that everything be in functions, and (2) look for a specially-named function that is designated to be the start function.

THis function is called main() for many programming languages.

Therefore, in keeping with convention, we will put all our programming statements (except for import statements) inside a main() function from now on.

The only programming statement that is not inside a function (e.g. that is not indented, not an import statement, not a def statement) should be the call to main()

def happy():

print "Happy Birthday to You!"

def birthday(name):

happy()

happy()

print "Happy Birthday dear", name

happy()

def main():

print "Say happy birthday to Grace"

birthday("Grace")

print "Say happy birthday to Lisa"

birthday("Lisa")

main() # This should be the only programming statement outside of a function definition (with the exception of import)

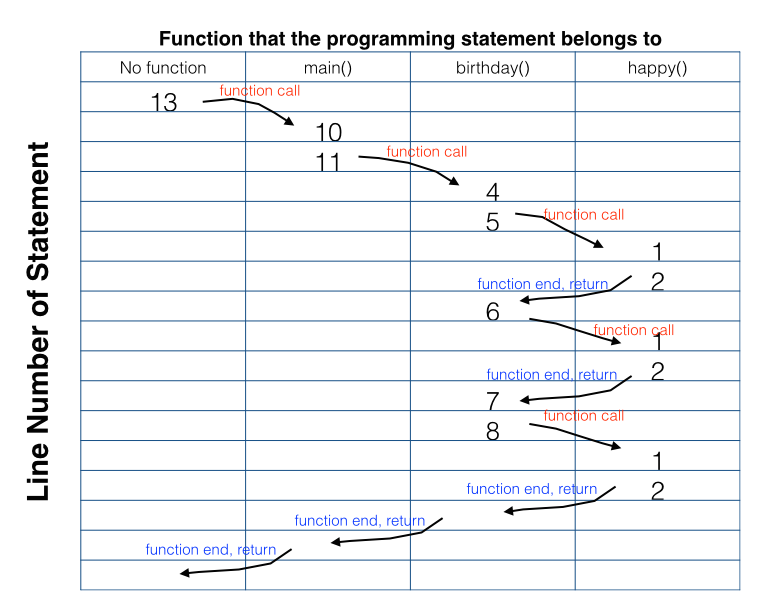

Programming Flow with Functions

Functions are another way in which we can change the flow of a program. When a function is called, Python skips to the location where the function is defined, runs the programming statements in the function, and then returns to where it left off.

Consider the following program with the line numbers as given:

1. def happy():

2. print "Happy Birthday to You!"

3.

4. def birthday(name):

5. happy()

6. happy()

7. print "Happy Birthday dear", name

8. happy()

9.

10. def main():

11. birthday("Grace")

12.

13. main()

14.

|

| Programming flow (order in which statements are executed) for above program. Note that lines 1 and 2 are executed multiple times -- each time corresponding to the happy() function being called |

Functions can also take more than one parameter. Let's use the childhood song "Old Macdonald had a farm" as an example:

(Song is at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5oYKonYBujg)

Old Macdonald had a farm, E I E I O

And on the farm he had a cow, E I E I O

With a moo-moo here, a moo-moo there, here a moo, there a moo, everywhere a moo-moo

Old Macdonald had a farm, E I E I O

If we change "cow" to "cat", then we need to change "moo" to "meow" (obviously). But the rest of the song is the same. This is a good place to use a function.

# This function will just play one verse

def sing(animal, sound):

print "Old Macdonald had a farm, E I E I O"

print "And on the farm he had a %s, E I E I O" % (animal)

print "With a %s-%s here, a %s-%s there" % (sound, sound, sound, sound)

print "Here a %s, there a %s, everywhere a %s-%s" % (sound, sound, sound, sound)

print "Old Macdonald had a farm, E I E I O"

print # Just a blank line to end the verse

sing("cow", "moo")

sing("cat", "meow")

# If we want to do multiple animals, it's easier just to wrap the function call into a loop:

def sing(animal, sound):

print "Old Macdonald had a farm, E I E I O"

print "And on the farm he had a %s, E I E I O" % (animal)

print "With a %s-%s here, a %s-%s there" % (sound, sound, sound, sound)

print "Here a %s, there a %s, everywhere a %s-%s" % (sound, sound, sound, sound)

print "Old Macdonald had a farm, E I E I O"

print # Just a blank line to end the verse

def main():

animals = ["cow", "cat", "dog"]

sounds = ["moo", "meow", "woof"]

for i in range(len(animals)):

sing(animals[i], sounds[i])

main()

# Note that when we call a function,

# we need to make sure that we use the correct number and type of parameters!

def sing(animal, sound):

print "Old Macdonald had a farm, E I E I O"

print "And on the farm he had a %s, E I E I O" % (animal)

print "With a %s-%s here, a %s-%s there" % (sound, sound, sound, sound)

print "Here a %s, there a %s, everywhere a %s-%s" % (sound, sound, sound, sound)

print "Old Macdonald had a farm, E I E I O"

print # Just a blank line to end the verse

sing("cow")

# Note that when we call a function,

# we need to make sure that we use the correct number and type of parameters!

def sing(animal, sound):

print "Old Macdonald had a farm, E I E I O"

print "And on the farm he had a %s, E I E I O" % (animal)

print "With a %s-%s here, a %s-%s there" % (sound, sound, sound, sound)

print "Here a %s, there a %s, everywhere a %s-%s" % (sound, sound, sound, sound)

print "Old Macdonald had a farm, E I E I O"

print # Just a blank line to end the verse

sing("cow", "cat", "moo", "meow")

Common mistakes:

You cannot define a function inside another function in Python. All functions are independent of each other

def sing():

def firstLine():

....When you call a function, all that is needed is the name of the function and the values of the parameter variables

birthday("grace")We do not need to write:

birthday(name="grace")Python will automatically match values (e.g. arguments) with variables (e.g. parameters) when the function starts, depending on:

- the order of the parameter variable names in the function definition, and

- the order of the values in the function call

You must have exactly the same number of arguments as parameters when you call a function

sing("cow", "cat", "moo", "meow")will not work. Python will choke when it gets to "moo" because it doesn't have a parameter variable in which to store the third value.

Why Use Functions?

Functions are not strictly necessary (it's always possible to write a program that doesn't have any functions), but they help programming in many ways:

- They make the code more modular. We can break down the code into little chunks that do specific things

- It also makes it easier to test for errors. It's much easier to test one little chunk for an error, than to test many many lines of code.

- It makes our code more readable. Assuming that we have good names for our functions (e.g.

testForEven(),getOneValue(),singOneVerse(), the function names help make our code easier to read (they're like variable names). - It makes our code more reusable. Later on, we will learn how to wrap a bunch of functions up into a library. This library can then be

imported into a program, just like therandomandmathlibraries, and the functions can be used.

Ultimately, we wish for our main() function to be just an outline that calls other functions.

Usually, my own rule-of-thumb is that if you have a function that goes on for more than one page, that's too long. Break it up into small modular functions.

While Loops

While loops are also called indefinite loops, because we do not know how many times they will repeat.

Indefinite loops keep on repeating until some condition is met.

For example: how to ask the user to input an even number?

Give me an even number: 3

Give me an even number: 7

Give me an even number: 1

Give me an even number: 2

Thank you!We do not know how many times the user will make a mistake. Therefore, a for loop won't work!

Indefinite loops are known as while loops in programming parlance.

Syntax

while <condition>:

do something

|

| Flowchart for while loop |

Illustration:

Consider the program testLoop.py in your inclass/w04 subdirectory. We can modify it to use a while loop instead of a for loop.

Psuedocode:

- Ask the user for

number - Initialize

i, the number I am going to print - While

iis smaller thannumber- Print

i - Increment

i

- Print

Exercise

Write a guessing game that will

- Pick a random integer between 1 and 100 (inclusive)

- Ask the user to guess until he/she guesses the right number

On every iteration, the program should tell the user whether his/her guess is too large, or too small.

The goal is to try to guess the correct number in as few tries as possible

Break

Chances are that in your last exercise, you wrote something like:

def guess():

number = random.randint(1, 101)

user_input = -1

while number != user_input:

user_input = int(raw_input("Guess the number I am thinking of: "))

if user_input < number:

print "Too low!"

elif user_input > number:

print "Too high!"

print "You're right!"This entails first initializing the variable user_input as a flag, or a sentinel. The purpose of the flag or the sentinel is to act as a signal to Python to indicate whether the while() loop is done or not.

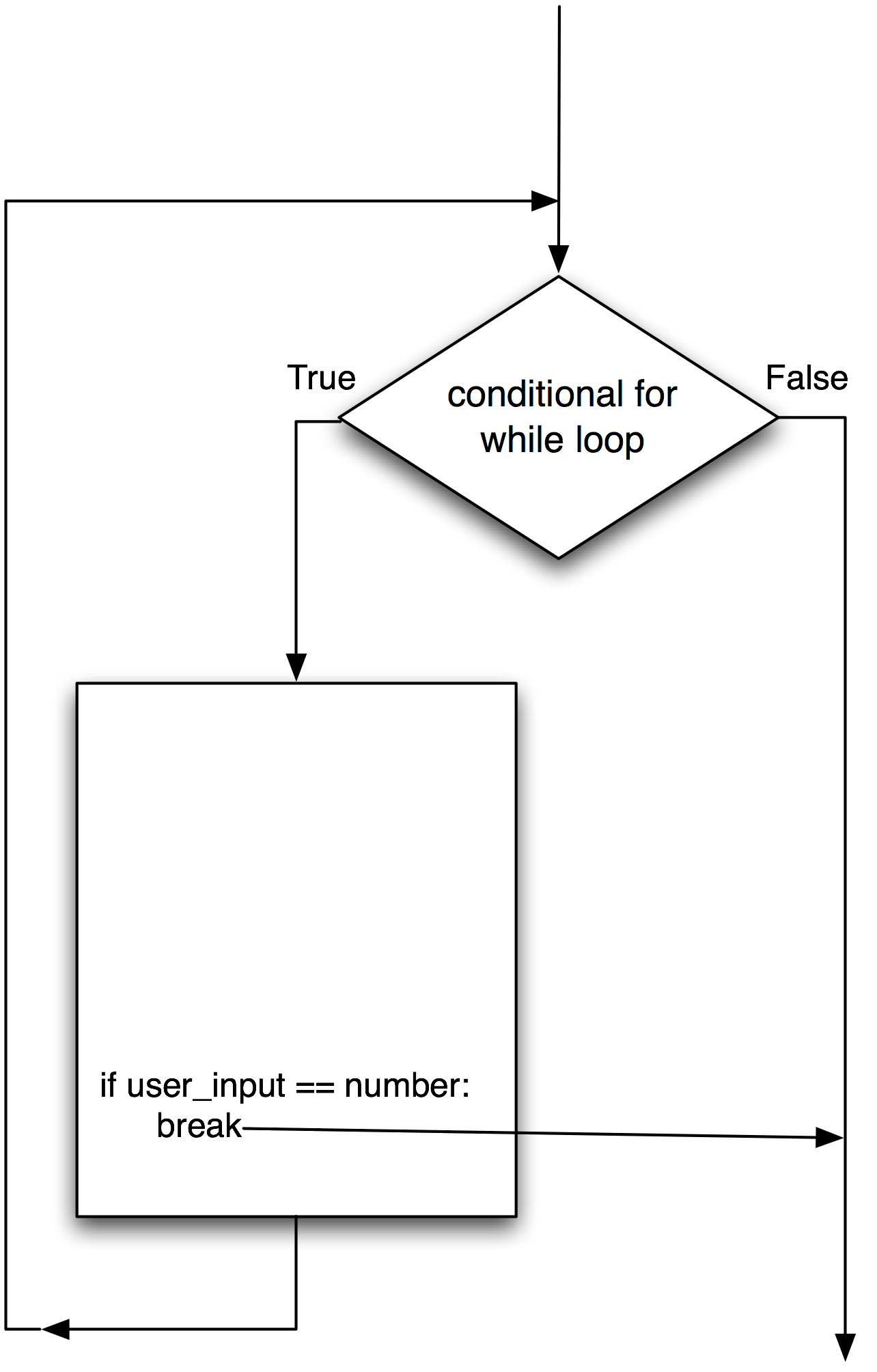

Turns out there's another way to terminate a loop in Python. We can use the break command. The break command immediately terminates the loop that it is in, and goes to the next statement:

import random

def guess():

number = random.randint(1, 101)

user_input = -1

num_guesses = 0

while True:

user_input = int(raw_input("Guess the number I am thinking of: "))

if user_input == number:

break # If we get here, we have guessed right, so we can get ot of the loop now

elif user_input < number:

print "Too low!"

elif user_input > number:

print "Too high!"

num_guesses = num_guesses + 1

print "You're right! You took", num_guesses, "guesses to get the answer"

guess()

As soon as the program encounters the break, it jumps out of the loop and goes to the next statement.

|

| Flowchart for break statement |

Breaks are not strictly necessary. You can always write a program without a break. But some programs are more easily written if you use breaks. For example, take our tennis-playing program:

- Initialize game_finished = True

- while (game_finished == True):

- Play a serve

- Update score of players

- Calculate if the game is done, update game_not_done if neccessary

Compare this with this approach:

- while (True):

- Play a serve

- Update score of players

- If player A has won this game or player B has won this game:

- break

It can be argued that the second approach is more easily understood than the first.

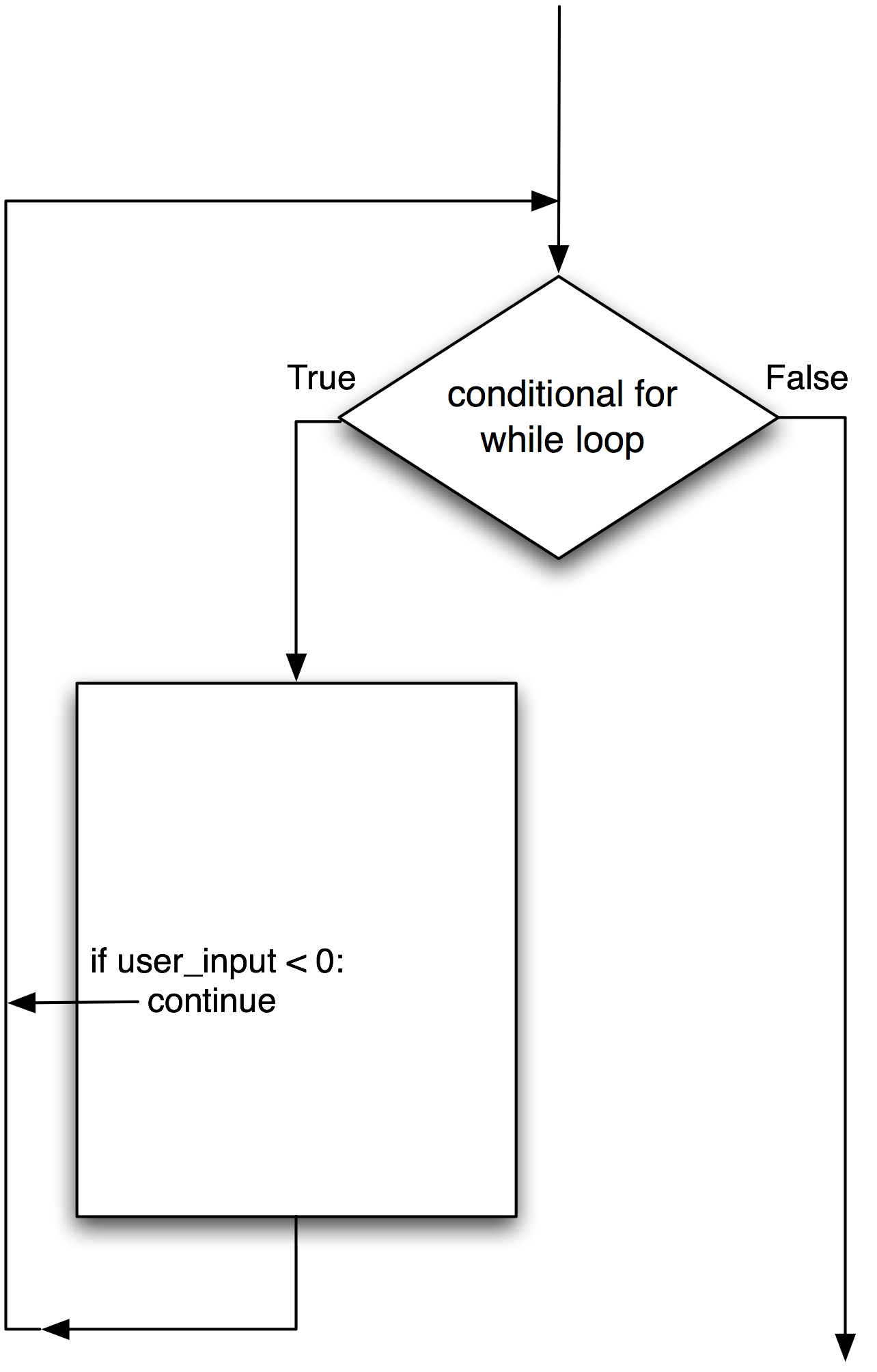

Continue

Continue is the another command that changes the flow of a program. It's like break, except that it skips over the rest of the statements in the loop, and then continues with the next iteration of the loop:

Let's say that we want to guard against the user putting in a stupid number (e.g. less than 0 or greater than 100). We can do a check that would skip over the rest of the programming statements if that happens:

import random

def guess():

number = random.randint(1, 101)

user_input = -1

num_guesses = 0

while True:

user_input = int(raw_input("Guess the number I am thinking of: "))

if user_input == number:

break # we got the correct answer, so end.

elif user_input <= 0 or user_input > 100:

print "I thought I said something between 0 and 100!"

continue

elif user_input < number:

print "Too low!"

elif user_input > number:

print "Too high!"

num_guesses = num_guesses+1

print "You're right! You took", num_guesses, "wrong guesses before you got the answer"

guess()

Note the number of guesses the program reports. It doesn't count the times when we enter in invalid input (i.e. <= 0 or > 100). That's because the continue skips the rest of the statements in the loop, including the num_guesses = num_guesses+1 line.

|

| Flowchart for continue statement |

Exercise (easy)

Write a program that will ask the user to input an even number, and repeat till the user gives a valid input.

Exercise (easy):

Average a list of numbers (e.g. list of scores) given by the user. But:

- we don't know how many numbers the user has!

- The user will signal that he/she is done by entering the empty string (i.e. typing an enter without anything in response to the raw_input)

- The user won't give invalid input (i.e. the user may enter an empty string or a number)

Exercise (harder):

In Lab 3, you wrote the encoding function for run length encoding. That is, you turned a string "aaaaabbbcc" to "a5b3c2". Now write the reverse decode function, that will take the encoded string "a5b3c2" and turn it back into the original string.

You can assume that each letter won't appear more than 9 times (in other words, you can safely assume that the encoded string consists of one letter followed by one digit followed by one letter followed by one digit.)