Monday

Welcome to CS21! My name is Jeff Knerr (pronounced "nerr"). I am teaching the MWF 10:30-11:20am section. This course is our first course in Computer Science (CS), so no prior knowledge of CS is required. If you have taken AP Computer Science in high school, or have a fair amount of programming experience (understand arrays, strings, searching, sorting, recursion, and classes), please come see me the first week to make sure you are in the correct class. This class is intended for majors and non-majors, but if you have significant programming experience, we may want to move you up to one of the next courses in CS (CS31 or CS35).

For our section we have two in-class ninjas: Saul and Thibault. If you get stuck in class or don’t understand something I am explaining, feel free to ask me or the ninjas.

My official office hours are on Fridays (12:30-2pm), but feel free to make an appointment for help or just drop by. I am happy to answer questions about class or lab work, or just review something for quizzes.

What We Will Do In This Class

The goal for this course is, obviously, to give you an introduction to Computer Science. We do that by teaching you the python programming language, as well as some basic CS concepts. Each week we will learn something new, and then write computer programs (lab assignments) to help reinforce what we just learned. In addition to learning to program, and learning about CS, you will practice and learn problem-solving. Designing and writing a program, as well as getting it to run correctly, involves a lot of problem-solving. Hopefully this is a skill that will help you in life, whether you go on in CS or not.

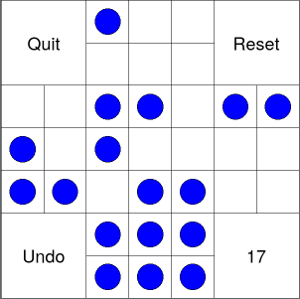

The HiQ game we looked at today is a good example of what we will do in this class. By the end of the course, you should be able to write a simple graphical puzzle/game, where the user clicks on boxes or pegs to move things around.

Developing and analyzing algorithms is also what we will do in the course. In your weekly lab assignments you will develop an algorithm and implement it in the python programming language. This includes testing your program, to make sure it works, and analyzing your algorithm, to make sure it is efficient.

This Week

For this week, you need to do the following:

-

attend your assigned lab session, on either Tuesday or Wednesday

-

start working on Lab 0 (due Saturday night) during your lab session

-

read the class web page!

-

if you forget your password, see our password service site

Let me know if you have any questions!

Wednesday

the python3 interactive shell

Opening a terminal window results in a unix shell, with the dollar-sign

prompt. At the dollar-sign prompt you can type unix commands, like cd and ls.

Typing python3 at the unix prompt starts the python interactive shell,

with the ">>>" prompt. At the python prompt you can type python code, like this:

$ python3 Python 3.6.8 (default, Jan 14 2019, 11:02:34) Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information. >>> 10 + 3 13 >>> 10 * 3 30 >>> 10 - 3 7 >>> 10 / 3 3.3333333333333335 >>> 10 // 3 3 >>> 10 % 3 1 >>> 10 ** 3 1000 >>>

The above python session shows some simple math operations.

To get out of the python interactive shell, type Cntrl-d (hold the control

key down and hit the "d" key).

data types

Data types are important. To the computer, 5, 5.0, and "5" are all different. Three data types we will work with are: integers (int), floats (any number with a decimal point), and strings (str). A data type is defined by the possible data values, as well as the operations you can apply to them.

For example, a string is any set of zero or more characters between quotes:

-

"A"

-

"PONY"

-

"hello, class!"

-

"1234567"

And only the + and * operators are defined in python for strings:

>>> "hello" * 4 'hellohellohellohello' >>> "hello" + "class" 'helloclass'

For numbers (ints and floats) all of the normal math operations are possible,

as well as a few others: +,-,*,/,//,%,**

>>> 5 / 10 # floating-point math 0.5

>>> 15 // 6 # integer division 2 >>> 15 % 6 # mod operator (remainder) 3

>>> 2**4 16 >>> 2**5 32

variables and assignment

We use variables in our programs instead of raw data values. Once we assign data to a variable, we can use the variable name throughout the rest of our program.

You can create your own variable names, as long as they don’t have any crazy characters in them (no spaces, can’t start with a number, etc).

The assignment operator (=) is used to assign data to a variable.

>>> name = "Jeff" >>> age = 50

built-in python functions

A function is just a block of code (one or more lines), grouped

together and given a name. We’ll learn how to create our own functions

in a bit. Python has many built-in functions we can use, like print()

and input(). You call a function using it’s name and parentheses.

Some functions just do something (like print data to the

screen/terminal), and others do something and return something.

For functions that return something (like input(), that returns what

the user types in), you usually want to assign what they return to

a variable.

Here’s an example of using input() and print() to get data from the

user, assign it to a variable, and then print it back out:

>>> name = input("What is your name? ")

What is your name? Jeffrey

>>> print("Hello, ", name)

Hello, Jeffrey

Some functions require one or more arguments (what is inside the parentheses).

The input() function requires one string argument, and this is

used as the prompt to the user. When input() is called, the prompt

is displayed, and then the function waits for the user to type something

and hit the Enter key. Once the user hits Enter, the input()

function returns whatever the user typed *as a string*.

In the above example the string "Jeffrey" is returned from input() and

immediately assigned to the variable name.

Why does this example fail?

>>> age = input("How old are you? ")

How old are you? 54

>>> print(age*2.0)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: can't multiply sequence by non-int of type 'float'

Remember, input() always returns a string. So the above fails because

python doesn’t know how to multiply a string (age) times a float (2.0).

type conversion functions

python has various type conversion functions:

-

int()— converts argument to an integer -

float()— converts argument to a float -

str()— converts argument to a string

Here are some examples, and one way to fix the above error:

>>> int("5") # convert string "5" to integer

5

>>> float("5") # convert string "5" to float

5.0

>>> str(5)

'5'

>>> int(3.14159)

3

>>> age = int(input("How old are you? "))

How old are you? 54

>>> print(age*2.0)

108.0

>>>

Note the nested function calls: int(input(…)) in the last example.

This means input() is called and returns something (the user input),

which is immediately sent to the int() function to be converted into

an integer. So age is assigned whatever the int() call returns.

the text editor (atom)

The last thing we did today was to write a full program using

the atom text editor. We first started atom on a new file:

$ atom racepace.py

Then typed in the following program:

"""

Marathon race pace calculator.

J. Knerr

Fall 2019

"""

def main():

distance = 26.2

pace = float(input("Marathon Pace? (min/mi): "))

totaltime = distance * pace # in minutes

print(totaltime)

main()The comment at the top (everything inside the triple-quotes) is just for us humans (to help explain the program), and is ignored by the computer.

The def main(): line defines the main() function, which is the

next four indented lines.

Finally, after main() is defined, it is called (the last line of the

file). If you save that in the file, you should be able to run the

program (from the unix shell) like this:

$ python3 racepace.py

Friday

writing a full program

We looked again at the full racepace.py program (see above).

Don’t forget:

- comment at the top

- def main(): to define the main function

- then call main() at the bottom (not indented)

And what happens if I unindent the print(totaltime) line?

Or if I put the call to main() above the definition of the main

function?

Also note my use of the distance = 26.2 variable. How would that change

if I wanted to show more than one distance, like this?

$ python3 rp3.py 1 mile pace? (min/mi): 8 For 3.1 miles: 24.8 minutes For 6.2 miles: 49.6 minutes For 10 miles: 80.0 minutes For 26.2 miles: 209.6 minutes

I could just have four different sections/calculations, but that would

be klunky. If I’m just doing the same thing over and over, with only one

variable changing (the distance), that’s what for loops are made for

(see below).

keyboard shortcuts

-

Alt-TAB — change focus from atom to terminal

-

up arrow — go through previous commands (works in unix terminal and in python interactive shell)

-

TAB completion — for unix commands, hit TAB key to complete filename or directory. For example: cd cs21/inTAB would complete to cs21/inclass

-

cd ..— moves UP one directory/folder -

cd— moves to home directory

So a typical workflow for me is:

-

open up terminal window,

cd cs21/inclass/labs/01 -

open up atom on a program:

atom burpees.py -

place the windows side-by-side, so I can see all of each

-

open a browser to the class/lab web page (also make it easily visible)

-

add something to the program in the editor

-

Alt-TAB to switch over to the terminal

-

python3 burpees.py(or just use Up arrow key) -

Alt-TAB to go back to editor, add some more code or fix something

-

Alt-TAB (back to terminal), Up arrow (python3…)

-

and so on…

for loops

Here’s another good example of the definite loop (a for loop in

python):

$ python3 times.py factor: 7 7 x 1 = 7 7 x 2 = 14 7 x 3 = 21 7 x 4 = 28 7 x 5 = 35 7 x 6 = 42 7 x 7 = 49 7 x 8 = 56 7 x 9 = 63 7 x 10 = 70 7 x 11 = 77 7 x 12 = 84

Here we get a factor from the user (in the above, the user typed 7),

then we display a times table for that factor.

The general syntax of a for loop is this:

for variable in sequence: do this and this and as many lines as are indented

The above loop would do those 3 lines of code with variable equal to the first item in the sequence, then again with variable equal to the second item in the sequence, and so on, for each item in the sequence.

The variable is just any valid variable name. You want to make it meaningful, but any valid name will work:

>>> for pony in [0,1,2,3,4]: ... print(pony) ... 0 1 2 3 4

Note: pony is not a good variable name (unless you are writing an

app about horses).

Let’s talk about the sequence. Examples of sequences (in python) are lists, strings, and files. For a list, the sequence consists of each item in the list. For a string, each character in the string. And for a file (which we won’t use until week 7), each line in the file.

Here’s a simple for loop using a string sequence:

>>> for ch in "abcdefg": ... print(ch*5) ... aaaaa bbbbb ccccc ddddd eeeee fffff ggggg

And remember, and indented lines are in the for loop code block.

The first unindented line is outside the for loop code block.

What do you think this code will print? How many "the end" lines will it print?

names = ['jeff','kevin','andy']

for name in names:

print("------------------")

print("hello,",name,"!")

print("the end.....")your turn!

Can you modify your racepace.py program to handle multiple distances?

I’m thinking something like this:

for distance in [3.1, 6.2, 10, 26.2]: calculate the totaltime based on distance and pace print out the total time